A Tale of Two Farrars - A Legacy of Disease

This is the story of two men named Farrar. Separated by over a century, both men became central to designing pandemic responses that would reverberate worldwide.

In early 2020, shortly after Jeremy Farrar had orchestrated the creation of the Proximal Origins of Sars-Cov2 paper, I began to investigate Farrar’s significant influence on global vaccine policy. However, my hunt for the truth eventually led me back to the turn of the 20th century, and to a man with almost exactly the same influence, in exactly the same arena. His name was also Farrar. This is the story of Reginald Anstruther Farrar.

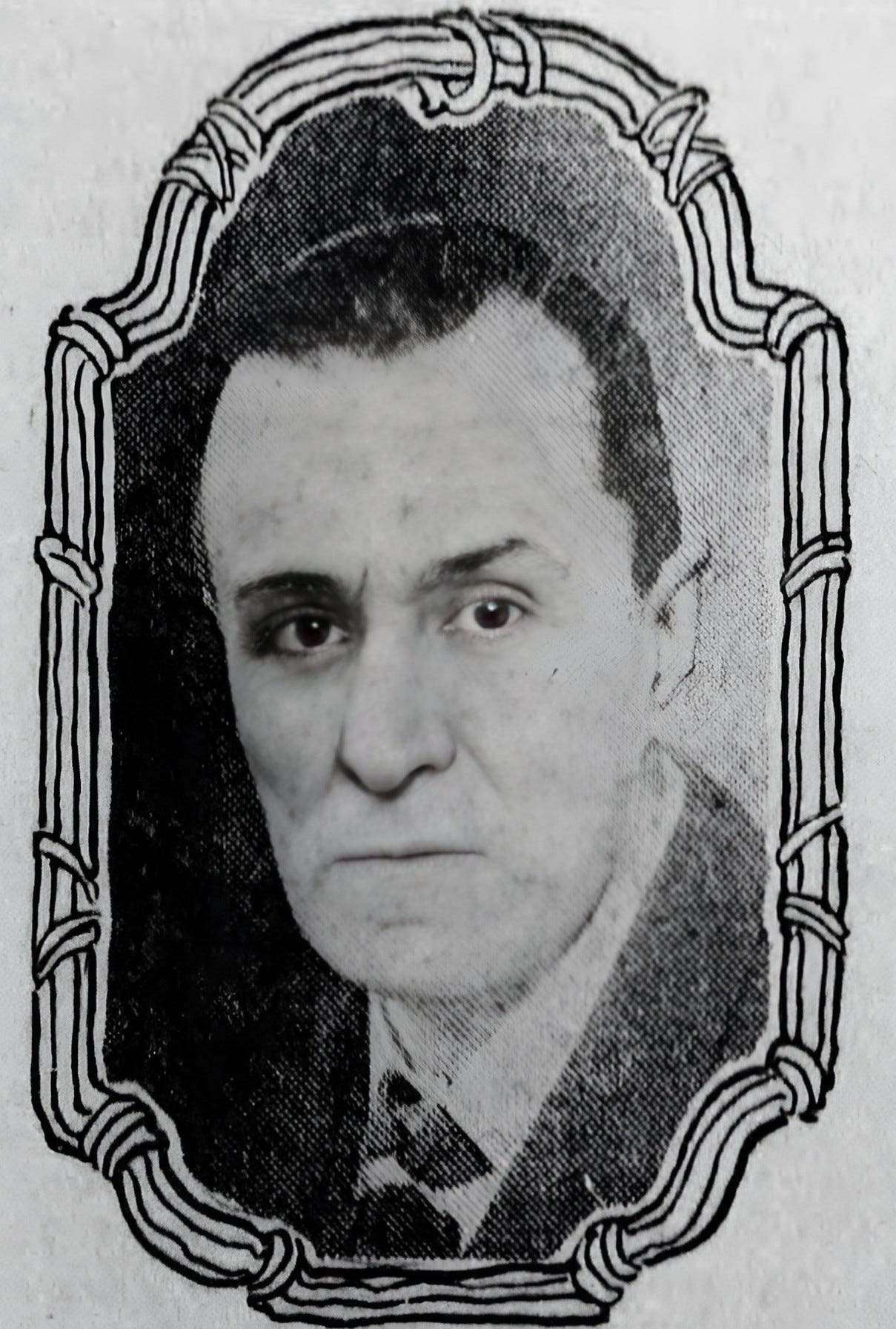

Reginald Anstruther Farrar was born on 14 May 1861 in Harrow, Middlesex, England. He was born to the Archdeacon of Westminster, Frederic William Farrar, and his wife Lucy Mary Farrar, née Cardew, and was their eldest child. As Reginald’s father was Archdeacon of Westminster, the family lived a privileged life from the get-go, however, he was also an extremely talented, fastidious, and astute young man, soon passing his matriculation examination for entry into Oxford University’s Keble College. Farrar’s eventual obituary describes the crossroads the young man reached during this period of his life:

“It was originally intended that he should take Holy Orders, but though always a religious man and actuated by the purest principles, he felt that he could not subscribe to the thirty-nine articles of the Established Church; he therefore turned his attention to medicine and became a medical student at St. Bartholemew's Hospital.”

Before heading off to university proper, Reginald Anstruther Farrar had been studying at Marlborough College, a public school which had been founded in 1843 specifically to school the sons of Church of England clergymen. On 19 October 1880, at the age of 19, Farrar officially became an undergraduate at Oxford University’s Keble College which had itself only been founded ten years prior, to stress “the Catholic nature of the Church of England”.

In 1883, Farrar gained his Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree at Oxford and continued to earn a Master of Arts (MA) and Bachelor of Medicine (BMed) degrees in 1889 and his Doctor of Mediation (DMed) qualification the following year. As mentioned, Reginald Farrar trained as a physician at St. Bartholomew's Hospital in London, a well-renowned teaching hospital. At St. Bartholomew's, Farrar was described as a flamboyant and likeable character:

“His loosely tied and flowing red cravat, stridcut [sic] voice, unconventional manner, enthusiasm, impulsiveness, and happy disposition, made him a well-known student at the hospital.”

He left St. Bartholomew’s in 1887. By 1890, he had passed his exams to gain membership to the Royal College of Surgeons making Reginald Farrar a fully qualified and highly skilled medical professional.

In 1888, Reginald A. Farrar married the fourth daughter of Canon Mapleton, who had previously been the Vicar of Meanwood, near Leeds, but by this time had become the Rector of Stamford. On 20 October 1888, the Yorkshire Herald newspaper reported that Reginald Farrar’s father referred to as the ‘Ven. Archdeacon Farrar’, was also Canon of Westminster and one of the ten ‘Chaplain-in-Ordinary’ to Queen Victoria. The wedding of Reginald and Mary Farrar took place in Goodrich Parish Church near Hereford on a Thursday afternoon with the ceremony being performed by the Lord Bishop of Hereford with the assistance of Reginald’s father, Archdeacon Farrar. Mary Mapleton wore a dress of “ivory white satin merveilleux” as she was given away by her father. Eric Farrar was reported as the best man for the marriage of Mary and Reginald.

In 1890, Reginald Farrar was listed as having a practice located at 60 St. Martin’s, Stamford. On 9 March 1891, Farrar officially became a Freemason, passing the nomination stage on 21 April the same year and being “raised” on 19 May 1891, as recorded in the United Grand Lodge of England Free Mason Membership Register. The 1892 edition of Kelly’s Directory—a publication which listed the business addresses of qualified medical practitioners—notes Farrar as working from St. Peter’s Vale in Lincolnshire. In 1893, Farrar took his MD and served in the position of house surgeon to Sir. William Savory prior to the latter man’s knighthood.

Then, in 1893, a tragedy occurred. Reginald Farrar’s brother-in-law and patient, Mr. David Hubert Mapleton, was found dead. Mapleton had seemed in good spirits according to another of his brother-in-law’s, Rev. Horace Annesley Powys, who was staying at Shillingthorpe Hall at the time of Mapleton’s death. At 11 am on Friday 28 April 1893, Mapleton spoke briefly with Powys in the study. Powys noted that Mapleton was in usual health and seemed very cheerful. As was reported in the Leeds Mercury 5 days later:

“The deceased [Mapleton} did not return to luncheon, and witness {Powys} went in search of him. He was told that Mr. Mapleton had gone fishing, so he proceeded to the river adjoining the hall grounds, and near a favourite fishing place he saw a lint on the water. He discerned a dark object in the river, and found it to be the body of Mr. Mapleton. He tried to restore animation, but unsuccessfully. Near the body was a fishing rod. On the previous day Mr. Mapleton had seemed particularly cheerful. Dr. Reginald Farrar, of Stamford, another brother-in-law, said that he had attended the deceased professionally for three years. His general health was fair, but he suffered sometimes from attacks of vertigo. Occasionally rather severely. At times the attacks were so acute as to render him insensible.”

The coroner who was assigned to the case came to the obvious conclusion from the evidence that the “deceased evidently fell into the river” and came to a verdict of: “Accidentally drowned”.

In 1894, Reginald A. Farrar began to publish articles and, over the proceeding decade, authored and edited medical literature. One of his first articles which publicly bore his name was written for the British Medical Journal and published on 13 October 1894 under the title, “Death Following Vaccination”. In the short article, Farrar refers to himself as a ‘Public Vaccinator’ which at the time was a relatively new official role. During this period, smallpox outbreaks saw compulsory vaccination processes implemented, yet, the tools used to vaccinate people were limited, experimental, and sometimes dangerous. The BMJ article written by Farrar discusses a case where he vaccinated a 5-month-old who died as a result of the process. Farrar paints a very distinct and definable process for vaccinating children, he stated:

“This child was brought to me on October 10th, 1893, for vaccination. She struck me as being rather small and thin for her age – 5 months – but otherwise had nothing obviously amiss. I did not, therefore, at the time see sufficient cause to postpone the vaccination, though in view of the poor development of the child I should have done so had the mother desired it. I vaccinated in four places, using a carefully cleaned lancet, and Dr. Renner’s calf lymph. Other children vaccinated at the same time, and from the same supply of lymph, did perfectly well in all respects.”

This was a rudimentary stage within the evolution of vaccination processes, and the procedure involved infecting healthy patients with a malady, a taboo principle for disciples of Hippocrates. However, the death that Farrar was reporting had resulted from the vaccination process administered by Farrar himself. He goes on to write:

“Instead, however, of the scabs drying up and separating in the usual times they persisted unduly, and from the intermixture of clotted blood, presented a “limpet shell” aspect, resembling rupial scabs. When at last they separated the ulceration was found to have penetrated the whole skin, exposing the muscles beneath, and leaving holes which looked as if they had been punched out. There was no oedema of the arm, and the skin round the vesicles appeared perfectly healthy throughout. The child “dwindled, peaked, and pined,” and finally died, from no very obvious cause, on November 29th, 1893, six months old, seven weeks after the vaccination, and about a week after the separation of the scabs.”

Farrar put the child’s death down to a “constitutional malaise, induced by vaccinia in a poorly nourished child.” Like many “vaccinators” of the era, Farrar was very careful not to rile up the very strong and vocal opposition who were battling against compulsory vaccinations, or even the idea of vaccinations en general. The same year in which Farrar wrote Death Following Vaccination, the Tamworth Herald produced articles such as “The Opposition to Vaccination” which reported on examples of widespread public disapprobation of what was becoming a commonplace, and sometimes compulsory, medical intervention. The aforementioned article states:

“In Mile End, London, says a London correspondent there are 8,000 unvaccinated children. The Guardians, armed by the law with power to judge whether an excuse for non-vaccination is reasonable or not, they naturally decide, in accordance with their antipathy to Jenner’s system, that any objection is reasonable. Supported by the great congregation who meet at Mr. Charrington’s large Assembly Hall, they look with confidence to the next election resolved to carry their opposition to vaccination still further.”

While some of the objectors were opposed to the vaccination process in general, many more were mobilised by the compulsory aspect of the relatively intrusive medical procedure. This same period also saw political controversy surrounding the late release of what was referred to as “The Vaccination Report”. The paper in question was the special report of the Vaccination Commission on Cumulative Penalties which was due to be released and contained information and statistics concerning the mass vaccination programs in England and Wales. The penalties for refusing vaccination had become a hot-button issue, and the aforementioned report made clear that these sorts of penalties should be abolished, as a Leicester Mercury article from the period put it:

“Defaulters under the Vaccination Acts should be treated more respectfully than pickpockets.”

Local Government Boards had been resisting calls by “antivaccinators” for the information to be made public which led to Arthur Balfour—who was then leader of the Conservative party—and Herbert Henry Asquith—who was serving at the Home Office—to calm the situation. The authorities had been shaken by the organisational prowess of those opposing compulsory vaccinations of all children as described in The Bristol Mercury on 20 May 1893:

“The medical profession are not likely to set up a political league to rival the organisation of the anti-vaccination faddists. They can only advise protection against smallpox, and marvel at the infatuation of those who neglect it. But their resentment of the runaway policy of the Government on Friday will be nonetheless serious because it does not express itself by public meetings, by hearty demonstrations, and by letter-writing rings, which Ministers just now appear over-willing to accept as “public opinion.”

It was clear that the Establishment needed systematic reorganisation if it wanted to sway, or control, what it would accept as “public opinion.”

From 1894, Farrar’s written work became more regular. Also in 1894, he published: “Sciatica associated with Iliac Abscess and Caries of Lumbar Vertebrae”, the following year he contributed to a piece entitled: “On the Clinical and Pathological Relations of General Paralysis of the Insane,” and, in 1897, he produced: “Case of numerous Hydatid Cysts Disseminated in the Abdominal and Pelvic Cavities.” But it was during the dying embers of the 1800’s and the turn of the new century when Farrar began writing his most important works. On 17 December 1894, Mary Farrar gave birth to a son with the news announced publicly in the Daily Telegraph four days later. In 1895, we also discovered that Farrar was active in local politics. A Lincolnshire Echo article notes him as a Conservative Party candidate for St. Mary’s Ward during the municipal by-elections at Stamford.

A Pox on Both Your Houses

In 1898, Reginald Anstruther Farrar left England for Bombay after accepting an appointment under the Indian Government, to take up plague duty. At 38 years old, Farrar was relatively young for such a position and was reportedly giving up a lucrative practice in Stamford. This move to India, in order to study a severe outbreak of bubonic plague, signified a vital turning point in the life of Reginald Farrar.

In 1901’s census, Farrar is noted as a 39-year-old ‘Doctor of Medicine’ from Harrow with a practice running out of 30 Ashley Place in London. In 1902, a paper on the nature of plague infection written by Farrar was read at the British Medical Association’s annual conference. Farrar had made some extremely vital observations about how the plague spread. The Savannah Morning News reported on some of his findings, stating:

“Before every outbreak among human beings in India, immense numbers of dead rats were found lying about. Whenever dead rats were found in the servants quarters of some particular house plague-striken patients from that house duly appeared within a few days at the hospital. Dr. Farrar found that plague did not spread along lines of human intercourse – like smallpox, for example – but was propagated by some sort of soil infection, always accompanied by the appearance of innumerate dead rats.”

In March 1903, it was announced that Reginald Farrar had been appointed as a medical inspector under the Local Government Board by its president, succeeding Mr Arnold Royle who retired. On 22 March that same year, Reginald Farrar’s father, Rev. F. W. Farrar, who was then Dean of Canterbury passed away. The following year, Thomas Y. Crowell & Co.. New York. published “The Life of Frederick William Farrar: Sometime Dean of Canterbury.” by Dr. Reginald Farrar. The book, which contained sixteen illustrations, a bibliography, and an index, had been a collaborative work with Farrar being assisted by various friends and colleagues of the late Dean Farrar. In England, James Nisbet & Co. published Reginald Farrar’s very public ode to his beloved father.

In 1903, Farrar also produced “Aids to Sanitary Science: for the Use of Candidates for Public Health Qualifications,” a training manual which is now available through the Wellcome Library. On 30 December 1904, the Tunbridge Wells Courier printed an article entitled: “The Farrar Memorial at Canterbury” which covered the unveiling of a new west window of the “Chapter-house” of Canterbury Cathedral dedicated to the late Dean Farrar, an event which was of course attended by Dr. Reginald Farrar.

By 1905, Farrar was becoming one of the United Kingdom’s leading experts on the spread of most diseases. In May of that year, an outbreak of spotted fever began to cause panic in a small town in Northamptonshire called Irthlingborough. Dr Reginald Farrar was sent in to investigate and claimed to have found a “distinctive micro-organism.” In a Manchester Courier article entitled “Spotted Fever,” it states:

“The cause of the outbreak was mysterious, and the sanitary conditions would not account for it. The only light that could be thrown on the matter was that Mr. Chambers, father of some of the victims, had received a paper from America, where the disease was raging.”

In March of the same year, Reginald Farrar again played a central role in the investigation of an outbreak of disease. Shining a light on poor rural sanitation had become an important part of Farrar’s work as a Medical Officer for the Local Government Board. In Clun, Shropshire, and Sleaford, Lincolnshire, “grossly insanitary [sic] conditions” were put under Farrar’s proverbial microscope, and on 15 March 1905, Dr Reginald Farrar began his inspections of Clun and Sleaford’s infamously unsanitary living conditions. In July 1906. Farrar was busy writing a report on how to clean up water supplies to various villages in North Wales. In the same year, he also wrote reports on “sanitary administration” in Durham as well as one on dirty dairies in Anglesey.

In February 1907, Farrar was recorded investigating the “sanitary circumstances” in the district of Gunthwaite and Ingbirchworth Parish Council on behalf of the Local Government Board. A few months later, in an article entitled “Hop-Picking Evils: Dr. Farrar on Conditions in Worcestershire”, it was reported that Reginald Farrar was investigating the lodgings and accommodation of hop-pickers and pickers of fruits and vegetables who were working in the county. The Daily Telegraph reported on Farrar’s findings, stating:

“That hop-pickers,” observes Dr Farrar, “are not as a class gravely dissatisfied with the provision made for them may be inferred from the fact that it is generally the custom for them to resort year after year to the same farm, retaining even a lien on the same hut. On one farm I heard of an old woman who died this year, but had previously picked there for forty-five years.”

The report written by Farrar on the hop-pickers was later referred to by David Lloyd George during questions in the House of Commons. Although the hop-pickers were often forced to live in cramped and unsanitary conditions, their plight was nothing compared to that of the navvies who Farrar was investigating during the same year. When reporting on the living conditions of the workers within Farrar’s Local Health Board report, the Guardian journalist wrote:

“There were not even any shelters to which they could resort in wet weather, and for a considerable time, they had to beg their drinking water from farmers and cottagers or drink that which was pumped up from the neighbouring river for engine use. Some of the workmen built rough shelters of fir boughs and corrugated iron, and nicknamed them respectively, “Firwood Avenue” and “Hotel Cecil.”

Cramped accommodation for workers during this period was commonplace around the United Kingdom. Farrar’s work inspecting such matters continued for the next few years, with him appearing in a later newspaper report entitled “Four Men in a Hen Coop”. His investigations eventually led to a report which was published by Wyman and Sons on 15 September 1909 with the catchy title “Report by Dr Reginald Farrar to Local Government Board on Lodging of Workmen Employed in the Construction of Public Works”, and was sold for 3 pennies.

Farrar’s main task wasn’t inspecting the living conditions of workers to assure compliance with regulations. In reality, Farrar was looking for disease. In February 1908, the Holyhead Anglesey Mail reported on orders given by Farrar and others to isolate any patients who arrived in port who may be suffering from the “plague of cholera”. A 1908 Post Office Home Counties Directory lists Reginald Farrar as practising from 7 Grove Park Gardens in the affluent Chiswick area of London, although it should be noted that another medical directory from three years prior stated Farrar’s practice as being run from 1 Grove Park Gardens.

At the end of 1908, Farrar was warning of the dangers of “tuberculous milk and flesh” after inspecting farmsteads where he discovered “the fold-yards ill-drained and filthy, and the cowsheds dark, dirty, ill-ventilated, and generally of insufficient capacity for the number of cattle they contained.”

In 1909, Farrar was reporting on “technical, though not legal, overcrowding” in Oldham, while also making a positive note on the “home proud” women of the town as being a credit to the region. In that year, he was tasked with reporting on the living accommodations of pea-pickers, the general living conditions of various navvies working nationwide, and he even wrote reports on the “evils of subbing”, the process of workers being continuously advanced wages, leading to them accruing significant debt.

On 30 August 1910, Farrar was tasked with visiting Melton Mowbray to investigate an outbreak of spotted fever. The Melton district reported 14 cases of the illness the previous week which led to Farrar’s impromptu visit. However, by the following week, the outbreak was being reported as having rapidly subsided, with the risk of infection as being slight.

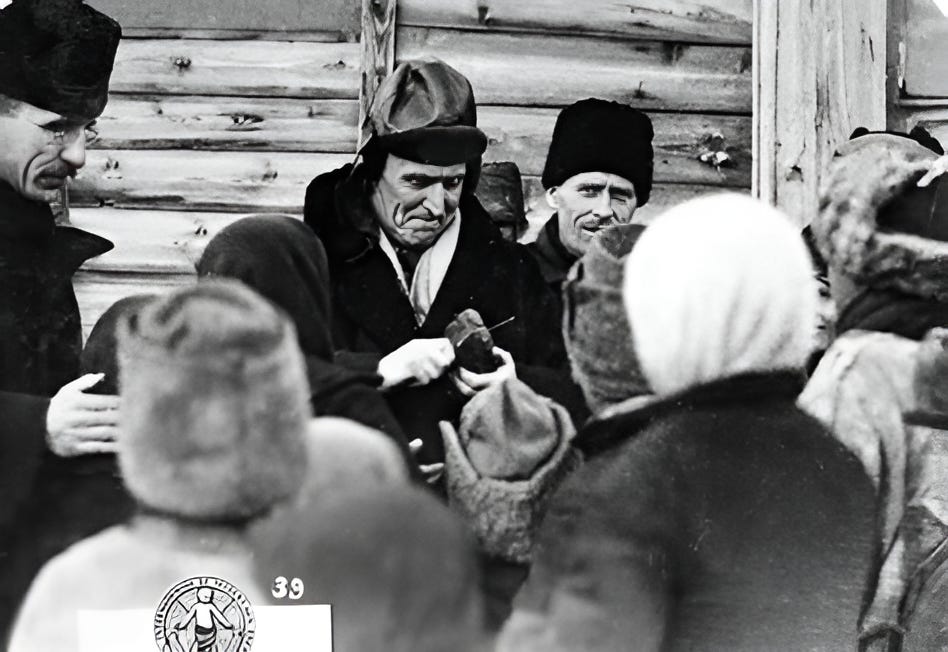

A Farrar Off Place

By 1911, Dr. Reginald Farrar had become an esteemed member of a very elite group of British infectious disease experts. He was nominated to represent Great Britain on the “International Plague Commission” which was set up to investigate an outbreak of pneumonic plague in China. Even though the plague in China was relatively under control by the time Farrar began to pack for the expedition, newspapers were reporting that he was being “sent to help Chinese to deal with scourge”. A message via the Reuter’s news wire from Peking during this time reported that about 7,000 people had already died during the outbreak. Farrar’s involvement in the International Plague Commission was being reported from Washington to Sydney, his basic biography was also reported in the Guardian Journal. A week later, Farrar was being praised in articles with titles such as “Heroic British Doctor: Going to China to Investigate the Plague” and “Guarding Against the Plague”.

The news of the pneumonic plague outbreak which was ravaging Manchuria saw a mild panic ensue in Western Europe. Even though the Brooklyn Daily Eagle were titling reports such as: “Plague Cases in England Were Detected on Ships Arriving from Manchuria”, this sort of bombastic reporting was soon dialled down a notch, with Farrar stating publicly that there was little danger of the plague spreading to Western Europe, let alone Britain.

Farrar’s involvement in the Manchurian outbreak led to him writing a report on his findings which gives us incredible insight into the evolution of pandemic response measures.

Initially, the Chinese had requested that Britain send Sir W J Simpson to attend their first ever international medical symposium, who had gained international fame for his work on plague in South Africa and Hong Kong. But this request was denied by the British, and they instead sent Reginald A. Farrar.

In the winter of early 1911, while Reginald Farrar studied the largest outbreak the Manchuria had seen for a long time, he made observations that would be fundamental for the British Establishment’s understanding of how populations respond to pandemics, and the conclusions of his following paper were astounding. Farrar didn’t only investigate the outbreak, and the procedures enacted to curb the spread of the plague, he was also in China to study the reaction of the local population to the spread of the disease. Farrar was quick to note the potential benefits which the psychological effect of a pandemic presented to changing wider social patterns of behaviour. In May 1912, in the epidemiological section of the Royal Society of Medicine Journal, Farrar published his findings in a paper ominously entitled, “Plague in Manchuria!”, Farrar begins the paper by writing:

“During the winter of 1910-11, Manchuria was ravaged by an outbreak of pneumonic plague, which recalls some of the historic outbreaks of the Middle Ages, but to which modern times afford no parallel. When compared with the mortality caused by bubonic plague in India, the actual proportions of the Manchurian epidemic do not seem large, but it captured the popular imagination by reason of the dramatic features which attended it, its mysterious origin, rapid spread, and appalling virulence.”

Farrar had previously been studying the Bubonic plague which had ravaged parts of India throughout the decade before. Millions had died in scenes that brought back Medieval memories of chaos and death to any European, especially in colonial Britain. Like during the worst years of plague-ridden British history, the Indian Black Death was of the Bubonic variety and was thought to be spread from human to human via infected fleas. Farrar reported that the Manchurian sickness was a solely pneumonic virus, spread from human to human mainly through the coughing of sputum into the localised environment. Although this was mostly true, the Manchurian Plague took three forms.

This period may have been relatively early in medical history, yet the scientists of Britain, Japan, China, and Russia, were all working on reproducing this virus in animals regardless of any potential dangers. The advances in technology meant they weren't only capable of isolating and identifying the specific strains of a virus, but they were also capable of reproducing the virulent plague cultures under very basic laboratory conditions.

As soon as the advances in technology allowed, scientists began doing a range of basic observational experiments. One Chinese colleague of Farrar had made their infected patients cough their sputum onto a new guinea pig every day for three weeks, only to note that every guinea pig died. Rats were injected with the pneumonic plague to see what would happen, and a free-for-all began on the scientific testing of the offending Tarabagan marmots, which had been the source of the Manchurian outbreak.

Reginald Farrar's paper, although over one hundred years old, is more relevant now than ever before for many reasons. In fact, one of the main purposes for Dr Reginald Farrar being sent to this remote deathscape was to examine the use of a very early experimental vaccination process.

When referring to the medical interventions being tested during the Manchurian epidemic, Farrar's notes give us a glimpse into the technology of the time:

“With regard to inoculation, Haffkine's prophylactic was tried a good deal. Dr. Martin inoculated him before he went out, and Dr. Petrie gave him another dose in the train. There was quite a long discussion on that point at the Conference. Galeotti was holding out for his serum, Martini for killed agar cultures, and Haffkine for Haffkine's prophylactic. Many patients who had been inoculated subsequently contracted plague, and died. Marmontoff had been injected three times, Dr. Jackson, he believed, twice.

Thirty-two patients inoculated by Haffkine at Harbin contracted the plague and died. There seemed to be some evidence that those inoculated were somewhat less liable to take the disease, but he did not think the Haffkine injection' was much of a success. If one had been recently inoculated, and in the negative phase, one might, some thought, be even more liable to plague than without such inoculation.”

Farrar also mentions the US appointment to the Chinese symposium, Dr Strong, testing out the potential of new vaccine technology, reporting:

“Dr. Strong fought hard for the use of attenuated living cultures, Dr. Strong had had exceptionally good facilities for testing this method. He was Government Surgeon in Manila, and his vaccine was a living culture attenuated with alcohol. After preliminary experiments on guinea-pigs, he satisfied himself, as the result of inoculation in 200 criminals who had been sentenced to death, that the attenuated living culture was as harmless as ordinary vaccine for variola.

Sixty-four of these criminals were afterwards inoculated with virulent plague culture and only sixteen died. They voluntarily submitted to the experiment as the alternative to execution. Though the method was not sufficiently appreciated by the Conference, he thought it held out great promise, and if he were going to face plague again he would have the attenuated living cultures inoculated.”

This was the birth of vaccine technology, and there were no limits.

Farrar's Manchuria paper had shown the British epidemiological Establishment something that they couldn't quite comprehend. They had failed at containing the spread of the Bubonic Plague in India, even while they were in control of all the administrative levers of power. Yet, these “Chinamen” (as the paper refers to them on occasion) were capable of achieving a significantly lower casualty rate, even without a state-of-the-art sanitary authority in place.

Dr Butler stated his scepticism that the Manchurian authorities have been responsible for controlling the spread of the virus which is noted in the discussion section of the paper, saying that:

“Of course, there was the point in favour of such administration that they were dealing with a disease which immobilized almost all who were attacked; there were very rapid effects, and universal death. That undoubtedly made the problem much easier than it would be where there were mild cases, which went about and diffused the disease among others. Still, it was difficult to believe that administrative measures could have achieved what had been depicted.”

But, Farrar soon pointed out during the discussion phase of his report that it was a matter of self-preservation which eventually controlled the infection. Isolation of the infected was not only practised on a case-by-case basis, but when neighbouring towns and regions became aware of this deadly virus running amok in other areas, they immediately closed off train lines and roads without needing to be ordered to do so. Responding directly to Dr Butler's scepticism, Farrar said:

“With regard to Dr Butler's remarks, he thought the members present had scarcely appreciated the fact that he said the crude efforts of the people had done much to protect the people from the plague. A person with plague was so ill, and all others had such a fright lest they should take it, that there was very little contact. People would not go near a house where the plague was, and when folks were roused, isolation thus effected was as effective as orthodox sanitary measures.

In Fu-chia-tien there was a very effective organization; the town was split into four divisions, and no person was allowed to go from one part of the town to another unless he or she had a pass. The divisions were indicated by different colours worn on the sleeve.”

In this paper, from over a century ago, we can see the formation of all the responses we still experience during a major pandemic.

The real surprise for the British scientific elites was the realisation that they had made a discovery that was before unrealisable. There was a significant link between the fear of a virus and the implementation of wide-reaching social control initiatives.

Whilst the British were busy bad-mouthing the Chinese and working off the information they had received from Farrar, they seemed completely unaware of their inadequacies in pandemic response. They displayed a systemic superiority complex that sabotaged the potential of a coherent collaboration. Manchuria had been a steep and useful learning curve for pandemic preparedness and every Western power would fail at the next test they'd be faced with.

The Story So Farrar

Reginald Farrar had stunned the British medical Establishment with his expertise, first in India, and then in the Far East. He continued getting opportunities and soon found himself working for the British Red Cross, the League of Nations, and the Norton Foundation. He had given great insight into, not only the spread of illness itself, but the way outbreaks can be used to enact sweeping measures which have the potential to change people's social practices, behaviours, and which rules they’re willing to obey. It became clear, that the threat of significant illness gave nation-states powers which could directly affect human behaviour.

In 1918, a World War I Medal Roll Index Card lists Reginald Anstruther Farrar as a potential recipient of an award referred to as the “1914 Star”. The document lists Farrar as achieving the rank of Major and notes him as a member of a local government board.

In 1922, Reginald Anstruther Farrar's death was recorded in the National Probate Calendar for England and Wales. It notes Farrar as a resident of Hillfield, Harrow on Hill, in Middlesex, and records Farrar as dying on 28 December 1921 at the German Hospital in Moscow. His son, Reverend David Mapleton Farrar is also listed as the clerk for the probate.

In February 1922, Reginald Farrar's death was reported in the Sunday Dispatch of London in a short announcement titled: "Died of Typhus," it read:

"A son of Dean Farrar, Dr. Reginald Anstruther Farrar, of Highfield, Harrow, who died of typhus fever at the German Hospital at Moscow while engaged with Dr. Naneen in the organisation of famine relief in Russia, left £1,997."

Almost 100 years later, Jeremy Farrar was to become central to the global pandemic response to the Sars-Cov2. There are glaringly obvious similarities between Jeremy and Reginald Farrar’s life. They both spent part of their careers studying sickness in East Asia, they both became central to analysing and incorporating official responses to the threat of deadly pandemics, and they both used previously untested new methods of inoculation on unwitting test subjects.

However, what may be most surprising about the stories of Jeremy Farrar and Reginald Farrar is that, although they were separated by a century of scientific discovery, both vaccinators seemed almost as clueless as each other about the actual benefits. Instead, both men were developing a branch of medicine which required a lot of human fuel to get correct. They were not afraid to push the boundaries of their science, seemingly without a care for the many human lives it would cost. Reginald Farrar was as central to the same Establishment at the start of the 20th century as Jeremy Farrar is today and it leaves us with one question in particular: Are Reginald Farrar and Jeremy Farrar from the same family?

To answer that question, I had to look at Jeremy Farrar’s father, Eric Farrar, who was born in 1917. I became even more curious when I discovered that Eric Farrar’s mother and father were meant to be 52 years old when he was born. Their previous child had been born 11 years before and it is very unlikely that two people in their 50s would have a child in 1917. Granted, it’s not impossible but, for any woman, the chances of falling pregnant past the age of 40 drop off considerably. That led me to investigate further and flung me down an unexpected rabbit hole with all roads leading to the Westminster elite who surrounded Queen Victoria and the British Royal Family. But that’s another story about another man who was also called Eric Farrar.